'Originality’ is in the composer’s personality

- Robert Muczynski,

Lecture on Composition, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, 5 November 1990

Introduction

To portray a composer’s musical aesthetic one must understand the intentions behind their music. These intentions can be made explicit via the composer’s background, context of works in her/his life, influences, recordings and indications given in a score. This hermeneutic approach is a way of understanding the whole as a sum of its parts (Beard 2005).

Robert Muczynski believed “that all one needs to know to perform his works is contained in the music itself.” (Cisler 1993, 59) However one might find it difficult to take a historically informed approach to understanding and performing Muczynski’s works as there is little to no information published about the composer. This essay investigates the most important paper on this subject to date; a doctoral thesis by Valerie Clare Cisler called The Piano Sonatas of Robert Muczynski, to gain a greater understanding of Muczynski’s Time Pieces op. 43 for Clarinet and Piano. An exploration of this text results in historical background, context and influences. Furthermore Cisler proposed the key features of compositional style found in Muczynski’s Piano Sonatas and such features have been identified in Time Pieces. Considering this background information and analysis, a more informed aesthetic for Time Pieces can be defined.

Muczynski’s piano writing is very distinct. His time lecturing and composing at the University of Arizona was spent during a period of favouritism for the avant-garde. Because Muczynski’s writing was not of this genre, he was labelled a traditionalist (Cisler 1993). This may be true in some respects but it is certainly not entirely so. While Muczynski was outcast for conforming to ‘traditions’, his determination and loyalty to his own expression resulted in a very unique musical voice – it is arguable that his music is of a postmodern nature, philosophically speaking.

When attempting to understand such a unique voice, the recordings of Muczynski himself performing his own works must be considered. These recordings depict his expressions and intensions. The recording of Muczynski performing Time Pieces with clarinettist Mitchell Lurie, who commissioned the work, will be the ultimate focus for the final part of this study. Bearing in mind the historical context, influences, compositional style and Muczynski’s own interpretations of his works, an informed description of Muczynski’s aesthetic is then made possible.

Robert Muczynski (March 19, 1929 – May 25, 2010 )

Background:

Muczynski was born in Chicago and was first introduced to the piano at an early age. He was obsessed with his grandmother’s player piano, especially because of the speed at which it played. He began piano lessons at the age of five and continued until he entered his Bachelor of Music at DePaul University, Chicago in 1947 (Cisler 1993).

At DePaul Muczynski studied piano with Walter Knupfer (student of Liszt) and began composition with Alexandre Tcherepnin in 1949 (1899-1977; son of Nicolay Tcherepnin). Both Knupfer and Tcherepnin disapproved of the time Muczynski spent practicing the other skill, so he eventually studied with Tcherepnin to be a ‘composer-pianist’. This facilitated his success at performing his own works (Cisler 1993).

Muczynski had early compositional successes. His first commission was awarded in 1953 from the Fromm Music Foundation and he composed his Symphony No. 1 op 5. The piece has never been performed. In 1954 his first piano concerto was commissioned by the Louisville Orchestra, subsequently this orchestra premiered and recorded this work with Muczynski at the piano. The following year Muczynski went on to perform his first piano concerto with the Louisville Orchestra in Chicago at Grant Park – almost 8000 people were in attendance (Cisler 1993, 22).

Muczynski taught composition from 1955 at DePaul and at Loras College, Iowa. He continued composing (opuses 8-10) then made his New York debut at Carnegie Hall in 1958, performing a programme of his piano works. In 1959 he received a Ford Foundation fellowship grant and was appointed composer-in-residence for the region of Oakland, California, for the purpose of writing works for high school students (opuses 11-14). This resulted in Muczynski being offered an exclusive publication contract with G. Schirmer, which lasted for thirty years (Cisler 1993, 24-5).

In 1961 Muczynski received a grant from the French Government to continue his studies with Alexandre Tcherepnin at the Academie de Musique, Nice. Whilst there he met the flute teacher Jean Pierre Rampal whose students were preparing Muczynski’s op 14, the Sonata for Flute and Piano. In the same year his flute sonata ultimately was awarded the Concours International Prize, likewise, his Suite for Piano received the International Society for Contemporary Music Prize (Cisler 1993, 25).

From 1961-1962 Muczynski was reappointed by the Ford Foundation and sent on a residency in Tuscon, Arizona (opuses 15-16, 18). In 1962 he was in receipt of a commission from the Chicago Little Symphony and he composed Dance Movements op 17 (Cisler 1993, 26).

Muczynski composed film scores from 1962-1964 (The Great Unfenced, Yankee Painter, American Realists). Also in 1964 Muczynski was invited by the Roosevelt University, Chicago, to be a visiting lecturer for the year. On returning to Tuscon, Arizona in 1965 he was appointed head of the composition department at the University of Arizona and remained there until he retired in 1988 as a Professor Emeritus (Cisler 1993, 27).

Muczynski’s chamber works were recorded in the late 70s by Laurel Records. Muczynski later decided to record his piano works himself as well. This was to provide performers a “primary resource for interpretive reference” (Cisler 1993, 33), as he had been asked for advice on his pieces on several occasions over time. His first album, Muczynski plays Muczynski was released in 1980. (Cisler 1993, 33)

Later that year the Concerto for Alto Saxophone and Chamber Orchestra op 41 was commissioned by saxophonist Trent Kynaston. He performed this work with the Kalamazoo Chamber Orchestra at Western Michigan University in 1981. This piece went on to be nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Music, in 1982 (Cisler 1993, 33).

Mitchell Lurie - clarinettist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra - commissioned the work Time Pieces, for Clarinet and Piano op 43 in 1983. It was premiered at the International Clarinet Society’s Clarinet Congress, London, in 1984 by Lurie and Muczynski. It was premiered in the US in 1987 by Charles Stier, clarinet, and William Bloomquist, piano, in Washington D.C. at the Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts. Stier then toured performing this work in Portugal, Barcelona, East and West Germany, Romania, Leningrad, Brussels and Prague (Cisler 1993, 34).

Muczynski’s ongoing success took him to the 1991 national convention for the Music Teachers National Association in Miami, where he was a guest composer. Time Pieces was one work amongst two full programs of Muczynski’s chamber music which was presented by US performers, including Muczynski himself on piano for his flute sonata (Cisler 1993, 31).

In 1992, Muczynski’s Second Piano Sonata op 22 was awarded the “best contemporary work” during the fifth International Piano Competition, Sydney, Australia. The competition winner also performed the work at the Ravina Festival, Chicago (Cisler 1993, 35).

Muczynski has had quite a successful career in his own right as a composer. Although his time spent at the University of Arizona was amongst unsupportive colleagues who labelled him a traditionalist, his music still managed to flourish and has had successes inside and outside the US (Cisler 1993, 417). It is therefore astonishing to find that there is a lack of information available on Muczynski: he does not even have an entry in the Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Harrold 2007).

Contex

American Music: The Compositional Climate

Musczynski’s American contemporaries were Charles Ives, Aaron Copland and Samuel Barber. His compositional output spanned from the 1940s to the early 90s. This places him as part of the period where 20th century American composers were finding their identities (Tischler 1986). This identity stems from being at the centre “of change and innovation in Western music”. (Tischler 1986, 92) Tischler also notes that

One important and interesting way to contribute to the acceptance of American music, irrespective of its intended national inspiration or message, was to compose modern music. (Tischler 1986, 92)

This idea of modern music included, Serialism, Dadaism, Futurism, Harmonic Polyphony etc. resulting from romantic music being deemed a “limited vehicle with which to compose the music of the new century.” (Tischler 1986, 93)

By 1935 the German composer, Hanns Eisler - who was in exile in America at the time – was a man with ‘revolutionary’ ideas. Not only did he believe that music can bring about social change and that it has a relationship to its environment, he also had an opinion on experimental music. Tischler summarises Eisler’s belief that:

Experimentation in modern music, no matter how interesting it may be to the composer, does not appeal to the public nor does it serve to resolve broader social issues of the day. (Tischler 1986, 116)

Eisler also believed that while composers debated the methods of creating the avant-garde, eventually a forthright man would come forward and “bang on the table,” demanding: “who does this benefit?” (Tischler 1986, 117)

Muczynski did happen to agree with Eisler on experimental music. Beauty, masterful composition, excitement, passion, conviction and positiveness are qualities that Muczynski prefered in music. To put it simply, he liked ‘GOOD’ music (Muczynski 1991).

When asked why he didn’t take a more experimental approach with his compositional methods Muczynski replied with:

I just didn’t want to write with my elbows! (Cisler 1993, 43)

Muczynski believed that the fashionable compositional styles such as twelve-tone Serialism were “rapidly atrophying… Diffuse writing is a cop-out and doesn’t require a heart/soul: only a brain.” (Muczynski 1991) He, and other composers (Copland, Roger Sessions) were afraid of music becoming dehumanised by methods of composition that were purely focused on arranging sounds and rhythms (Cisler 1993, 53)

Aaron Copland believed that composing in this intellectualised manner promotes an

attitude… of avoiding the whole messy business of aesthetic evaluation, putting one’s attention on workmanship and craft instead… But that attitude… side-steps the whole question of the composer’s own need for critical awareness and for making aesthetic judgements at the moment of creation. (Copland 1952, 45)

Muczynski was always reluctant to talk about his own compositional processes. Cisler points out that this is in no means due to a lack of knowledge as he was a very well informed musician. She instead offers two examples of Copland’s compositional processes as possibilities. These processes were firstly; a hallucinatory state where there is a duality of mind - a dictator and a scribe, and secondly; a state of inspiration where the personality loses sight of the whole mind in a “spontaneous expression of emotional release.” (Cisler 1993, 53).

One may infinitely speculate the possible ways in which Muczynski worked. The decisions he made in his compositions were fundamentally based on one element: that which sounded good to him. All other apparent processes are less important to the character and quality of a work (Cisler 1993, 51).

I don’t know half the time what [my music] means: I compose instinctively, intuitively – by ear.

- Robert Muczynski (Cisler 1993, 122)

Influences

It was difficult to determine Muczynski’s style, or his aesthetic, due to his unwillingness to speak of his influences as well as his processes. Cisler has suggested the composers Muczynski “respected and admired”; those who she has found through her own interviews of Muczynski and his colleagues (Cisler 1993, 58). She has deduced the following composers had the greatest influence:

Early years: Beethoven, Liszt

Slightly later: Prokofiev, Bartok, Copland

Through his Career: Barber

Cisler then offered his other favourites: Vivaldi, Haydn, Chopin, Brahms, Frank, Debussy, Shostakovich, Hindemith. Also his favourites in ‘popular genres’:

Gershwin and film composer Max Steiner (Gone With the Wind etc.) (Cisler 1993, 59). Muczynski was also influenced by big band, jazz, ragtime, blues and ballads while he was growing up in Chicago throughout the 1930-40s (Cisler 1993, 84).

From his earlier years of study, the compositional text book that inspired Muczyski the most was The Homophonic Forms of Musical Composition by Percy Goetschius. Goetschius stated in his book that all good compositions have both ‘variety’ and ‘unity’, ie. a variety of stimuli and a unification of the ideas to create an organic whole. Goetschius also identified that variety must have unity and that unity must have variety. These two concepts could be related to the two sides of aesthetics – the objective and the subjective; the rational and the emotional; things known and things perceived (Beard 2005).

Goetschius follows the rules of tertian harmony in his book. He believes that one must state their musical idea clearly and simply first, so that the listener can comprehend the musical ideas which will be developed later. He also advocates “the four most important requisites for successful musical composition:”

- comprehension and command of tone

- fertile imagination

- strong and balanced intellect

- emotional passion (Cisler 1993, 121-2)

Muczynski’s most inspiring teacher was Alexandre Tcherepnin. Tcherepnin was a composition lecturer at DePaul University, Chicago. Muczynski was one of his first American students. Tcherepnin was a good match for Muczynski in the sense that his teaching methods fit in with Muczynski’s own sensitive nature. He always taught with a positive attitude towards his students. He helped them develop their individuality and musical intuition and would draw upon their potential rather than be overly critical (Cisler 1993, 61).

Tcherepnin… helped give [Muczynski] the strength and confidence to honour the conviction to compose (express musically) what he felt within himself… (Cisler 1993, 63)

Muczynski’s own personality is reflected in his music. His partner, concert pianist Richard Faith believed his intensity and ‘self-demanding’ qualities were evident in his compositions. A colleague, Karl Miller, believed that his unease with himself and his shyness reflect the intimacy in his music and his preference for writing chamber music. Also that his sensitiveness and emotional nature promote excitement in his music; that when his life was unbalanced, his “truest” pieces were created - showing an overpowering ‘troubled nature’ (Cisler 1993, 128-9).

Muczynski’s later works appear to have developed into a more mature state. A culmination of his ideas. Leigh Harrold, when talking about Muczynski’s three piano sonatas, describes his “compositional evolution – from wayward pioneer to idiomatic virtuoso to refined sophisticate.” (Harrold 2007). He also believes that because Tuscon is so close to the boarder of Mexico, Muczynski could have spent time in South America and or at least been influenced by its music – namely Alberto Ginastera and his piano sonatas (Harrold 2007). This does show in his later works such as the Third Piano Sonata, Twelve Maverick Pieces and in Time Pieces. The latter two of these works actually share a lot of thematic material, which is an interesting point to raise. Muczynski disliked music that was ‘derivative’ (Cisler, 1993) yet he was not afraid of re-using his own ideas (Harrold 2008).

In terms of the South American influence on Time Pieces, Harrold also recounts his own experience with the work:

In a masterclass I once participated in, playing Muczynski’s Time Pieces for clarinet and piano, the master clarinettist David Shephard – who had discussed the work with Tuscon clarinettist John Denham – said that the brusque semi-quaver triplet figures in the piano part had to sound like clattering castanets, while the heavy regular chords in the bass were the ‘foot stomps of a Flamenco dancer’. (Harrold 2007)

The afore mentioned influences are present in Muczynski’s compositions. These influences will be identified in Time Pieces in the following two sections. However it is not possible to know whether he did follow any specific formulas of composition, such as that of Goetschius. While Muczynski did not follow any set system or process of composing and his methods differ from work to work, he was a perfectionist with his writing (Cisler 1993, 122-3).

Postmodernism

Postmodernism is a term coined to describe the philosophical thought that comes after Modernism. This way of thinking is contemporaneous with Muczynski’s career as it began in the 1950s. In practice postmoderism is a way of thinking about present times in a historical manner. Postmodern theorists reject the emphasis on meta-discourse (a totality of thought/knowledge) and the grand narratives (large scale cultural ideals) of the past and in place wish to emphasise the little narratives (Beard 2005). Postmodernism is arguably a hermeneutic look at human discourse. It takes each micro-narrative into account which is an act of removing the parts from the whole – ie. for singularity or fragmentation. Plainly, that in no case is there one answer to everything (however this concept is therefore an answer or Truth claim in itself. Such contradictions are a problem faced by anyone who attempts to define postmodernism).

With this statement in mind, perhaps one can treat Robert Muczynski as a postmodernist composer. He was not concerned with the fashionable methods of composition throughout his life, yet he did not reject them purely for the reason of actively seeking individuality. This is also not to say he was devoid of influences. Beard states that when applying postmodernism to music there needs to be a lack of dominant cultural beliefs. (Beard 2005) Muczynski’s influences came from a variety of different cultures. There is arguably no cultural belief that dominates. These cultural influences combine and permeate his music to create something entirely original. His body of work exists irrespective of the compositional trends of his time and he was able to stay true to his own musical beliefs. Muczynski’s position in society is postmodern as is his music.

Key features of compositional style

- Traditional forms and diversions from them;

Four pieces/movements, sonata form:

I. Allegro risoluto (sonata allegro)

II. Andante espressivo (ternary)

III. Allegro moderato (ternary; scherzo and trio)

IV. Andante molto - Allegro energico (intro - rondo)

Piece no. II diverts from expectations in its fluctuations in themes and tempi, however it is still noticeably in ternary form:

A: andante crt=52 - meno mosso, (crotchet) = 40 – tempo I

B: poco piu mosso, crt=63 – meno mosso, crt=40 – (A+B) subito piu mosso, crt=52

Cadenza (A): andante, crt=46

A: tempo I

A2: adagio, crt=42 – lento

- Themes that differ in tempo/time signature as well as tonally;

- Also in piece II, as shown above.

This stylistic feature creates the following two features:

- Narrative sectional construction &

- Lyricism v Percussiveness;

Muczynski uses vastly differing themes to create a narrative like structure. Furthermore he creates contrast with lyricism and percussiveness. This is evident in pieces II and IV:

IV

Introduction: andante molto, expressivo; lyrical, mp, consonant

A: Allegro energico; percussive, f, dissonant

B: lyrical, mf, consonant

A: percussive as before

C: lyrical as before

Cadenza (A): furioso; percussive phrase – lyrical phrase x3

Coda (A2): percussive as before

- Combining themes;

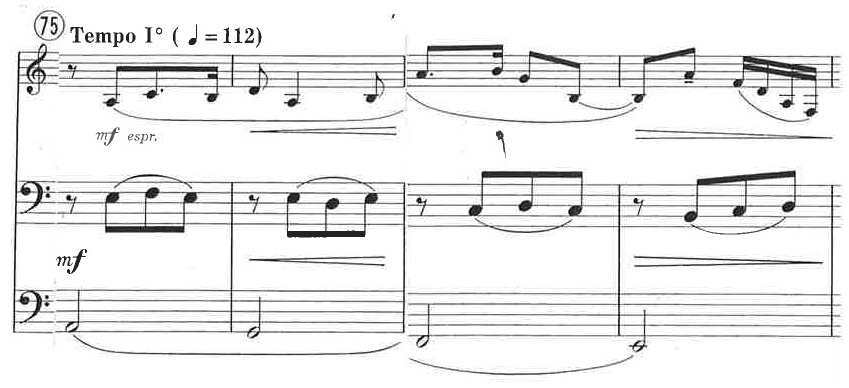

in piece III the theme of the A section is combined with the B section theme in bars 41-45 :

Example 1

- Cyclicism:

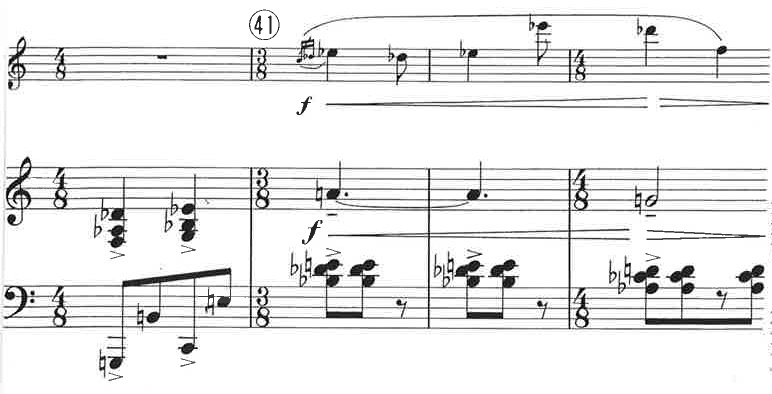

in the development section of piece no. I, foreshadowing of a theme from the fourth piece is used:

Example 2

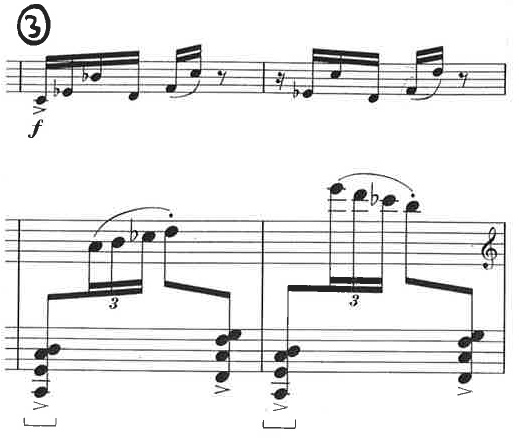

- Rhythms; 'speech like' or motor.

There is a speech rhythm immediately followed by a motor rhythm in piece I, second theme, in both instruments:

Example 3

- Signature Rhythms;

3+3+4 or 3+3+3+3+4 (3+3+2)- the first theme of piece IV,

- bars 48-49, in piece I:

Example 4.1

Example 4.2

- Syncopation motif

strong bass down beat, syncopated melody - as at opening of piece:

Example 5

- Ostinato:

Ostinatos are frequently used by Muczynski. This can be seen in bars 12-24 of piece I, in the bass of the piano, then again in bars 39-41:

Example 6

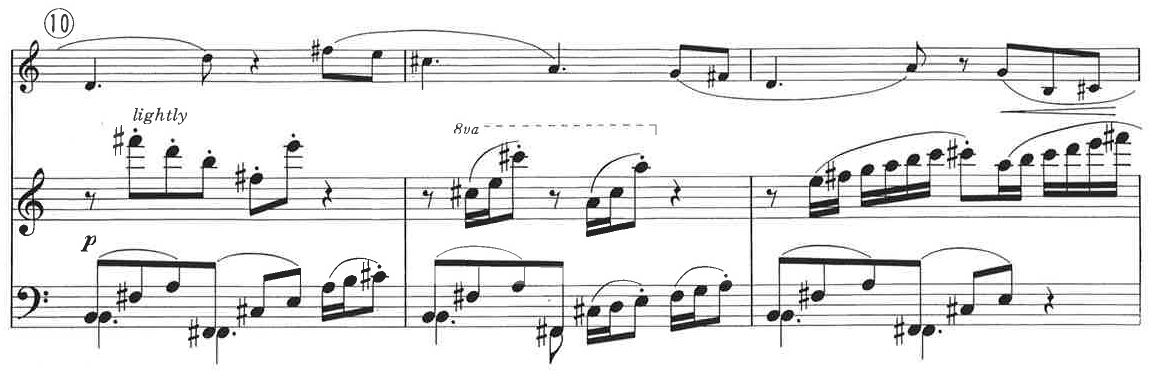

- Polyrhythms;

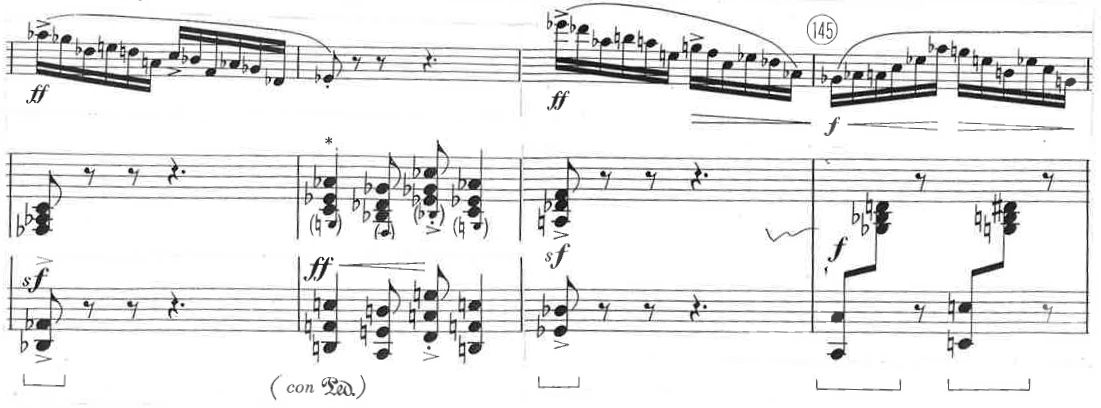

An instance of polyrhythms is firstly in the example above. Another instance is in piece III from the clarinet entry in

bar 10:

Example 7

- Tertian harmonies,

- Semitone modulation &

- The Blues scale;

piece III has examples of these three points. The piece begins in D major following tertian harmonies. The trio section, instead of being in the dominant key of A major, is in Eb major – a semitone modulation. The scale of Eb features the flattened third, Gb, and seventh, Db, which resembles a blues scale.

Example 8

- Bimodality;

the conclusion of piece III is an example of bimodality as Muczynski combines the D major and Eb blues scales to create the final run of semiquavers for the clarinet and the final chord of the piano. This run is another example of cyclicism as it concludes piece IV:

Example 9.1 - 9.2

- Strong Cadences

- Angular melodies

- Layered textures in slow movements

poco piu mosso in piece II – ostinato, messlody and counter melody:

Example 10

- Grotesquerie &

- Surprises

melodic distortion, unexpected harmonic shifts, octave displacement;

Piece IV end of C section:

Example 11

Muczynski Plays Muczynski

Technically and musically there is quite a lot going on in this four-movement suite, and much of the time both instruments share the action equally. The music is made up of a number of elements: energetic, syncopated rhythms, long and sustained melodic lines, cadenzas for solo clarinet, tongue-in-cheek humour and an overall “up” feeling. For me the title refers to when and where I was composing the work, sort of a frozen-in-time idea. (Muczynski 2000)

On hearing the piece as played by Muczynski and Lurie, it is easy to distinguish that it is in sonata form. The first movement opens with percussive rhythms (castanets) in the piano – Muczynski plays these rhythms more loosely perhaps in keeping with his South American influences. A bold, declamatory, syncopated theme is stated by the clarinet which indicates influences of jazz; especially as one hears consecutive dominant 7th chords which Cisler identifies as a characteristic of Muczynski’s “jazz flavour”. (Cisler, 1993, 95). The 3+3+2 rhythms at the same time give a South American feel. In places the Lurie seems to take on the role of a soloist in a big band with his fanfare like phrases. This movement has an edgy and excitement about it. When a more lyrical ballade like phrase comes in during the development section of the movement it creates a feeling of relief before a textural and dynamic climax.

The second piece is very intimate. It reflects Muczynski’s more emotional side and possibly troubling times in his life. Lurie plays the lamenting opening theme with a touch of vibrato to accentuate the expression. the free use of rubato suggests a romanticism in the singing of the melodic line. This theme progresses to a ballade like second section. Following this one can hear a more aggressive tango which again utilises a 3+3+2 emphasis – Lurie uses more length on the accents of the first and third beats while Muczynski employs angular accents and highlights the syncopation to depict this South American style. Following this section, Lurie freely plays a solo clarinet interlude which is a broken quote the opening theme. This solo develops into song like section utilising rubato, before recapping the opening theme.

The third piece sounds much like a tango. On first impressions it is perhaps reminiscent of Leonard Bernstein’s sonata for clarinet, or other composers of a 'popular genre’ such as Gershwin. It is a happy sounding movement with a positive and also perhaps comical nature that permeates. This is demonstrated by the sweeter tones of the clarinet and a more approach semplice to the theme. Muczynski adds light interjections which sound improvised jazz riffs – again one can hear this combination of jazz and South American styles. This has quite an uplifting effect as this mood has not yet been present in the work.

The final movement opens with a clarinet solo passage. This is quite reflective in feeling, again with a touch of rubato. Lurie depicts emotional outbursts then settles again before leading into the main theme. This theme is percussive and syncopated, Muczynski then creates the flamenco foot stamping with his bass note accents while Lurie mimics castanets with his triplets. It leads then into a section which Lurie plays with a jovial spirit, almost like a popular song; perhaps in the same vein of Bernstein/Gershwin as before. The theme comes back after which the listener is given a quote from the third movement as if in jest. This quote is played with the same semplice approach which provides great contrast in character. The next section is played more aggressively, almost as though Muczynski and Lurie argue in call and response. Lurie wins, launching into a furious cadenza. Here he shows contrast in character with a forceful percussive line followed by a lyrical line. He then toys with previous motifs and melodies before winding back into a declamatory motor rhythm. The piece concludes with the same bimodal scale from the end of the third movement, however finishing at a more triumphant height.

Conclusion

Muczyski and Lurie demonstrate a vast amount of Muczynski’s influences in their performance. The meter and accentuations are favoured over rhythmic accuracy to indicate the stylistic influences. Rubato and vibrato are used to show emotion, especially in the slower and more lyrical sections. It is therefore be inadvisable to interpret this work in a modernist American style whereby treating it in a precise, objective manner. Muczynski and Lurie perform this work in a way that suggests the emotional and stylistic intentions are paramount throughout the work. More poignantly, it is arguable that a more accurate interpretation of this work is that it is a postmodern amalgamation of a variety of styles. An aesthetic can therefore be summarised using these characteristics:

- Jazz

- Popular American classical music

- South American, such as Tango and Flamenco

- Ballade

- Romantic

- Positive

- Percussive v lyrical

Muczynski welcomed free interpretations of his works as this “keeps things lively” (Muczynski 2000). However it is argued that freedom of interpretation must come within the above characteristics if one is to take an informed approach to this work. If one considers the composers intentions and therefore his own aesthetic - as it has now been postulated - Time Pieces can be performed as a unique and well rounded piece of music.

Bibliography

Books

Anderson, R 1976, Contemporary American Composers; A Biographical Dictionary, G.K. Hall & Co., Boston.

Arias, E.A 1989, Alexander Tcherepnin : a bio-bibliography, Greenwood Press, New York.

Austin, W.W 1966, Music in the 20th Century, W.W. Norton & Co. Inc, New York

Beard, D & Gloag, K 2005, Musicology: the key concepts, Routledge & Kegan Paul, New York.

Butterworth, N 1984, Dictionary of American Composers, Garland Pub., New York.

Copland, A. 1952, Music and Imagination, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

Hamilton, A 2007, Aesthetics and Music, Continuum, London.

Hansklick, E 1986, On the Musically Beautiful: a Contribution towards the revision of the Aesthetics of Music, trans Geoffrey Payzant, Hackett Pub. Co., Indianapolis.

Hinson, M 1987, Guide to the Pianist’s Repertoire, Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Kay, E ed. 1988, International who's who in music and musicians' directory, 11th edition, Melrose Press, Cambridge.

Korabelnikova, L 2008, Alexander Tcherepnin; the Saga of a Russian Emigré Composer, trans. Anna Winestein, Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Tischler, B.L 1986, An American Music; the Search for an American Musical Identity, Oxford University Press, New York.

Periodicals

Simmons, W 1975, What is Today’s Music?, Musical Opinion 98, May: 403-404

Dissertations

Cisler, V.C 1993, The Piano Sonatas of Robert Muczynski, DMA diss, University of Oklahoma

Musical Scores

Muczynski, R. 1990 Collected Piano Pieces, ed. 1972, G. Schirmer Inc, New York

Muczynski, R. 1985 Time Pieces, for Clarinet and Piano op 43, Theodore Presser Co, King of Prussia, PA.

Correspondence

Muczynski, R, Tuscon, to Valerie Clare Cisler, 1989-91

Discography

Andrist, A 1999, Spontaneous Lines, (Rokeach, Currier, Muczynski, Maggio, Bassett), Performed by Audrey Andrist and Nathan Williams, Albany Records.

Gorokholinsky, A 2002, Time Pieces, (Stravinsky, Debussy, Milhaud, Kovacs, Ravel, Muczynski, Bozza) Performed by Alexey and Marina Gorokhilinsky, Classical Records.

Muczynski, R 2000 Robert Muczynski Composer, Pianist – In Recital, vol 2,

(Seven, op. 30; Duos for Flute and Clarinet, op 34; Third Piano Sonata, op. 35; Twelve Maverick Pieces, op. 37; Masks, op. 40; Time Pieces for Clarinet and Piano, op 43; Desperate Measures, op. 48), Performed by Robert Muczynski, Julius Baker and Mitchell Lurie, Produced by Herschel Burke Gilbert, Laurel Record, Los Angeles

Saiote, A. 2006, Clarinete do nosso tempo, (Bernstein, Muczynski, Poulenc, Saint-Saens) Performed by Antonio Saiote and Pedro Burmester, Saphir Productions.

West, C 1996, Piano & Clarinet, (Lutoslawski, Faith, Genzmer, Delmas, Alwyn, Muczynski), Performed by Charles West and Susan Grace, Klavier.

Electronic Sources

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanns_Eisler

Other

Harrold, L 2007, ‘Best since Barber’: Contextualising the Piano Sonatas of Robert Muczynski, lecture-recital.

Harrold, L 2008, Notes on Cisler’s Dissertation.